Please note: This blog post is a course related assessment for the Master of Arts in Learning and Technology program at Royal Roads University.

For Activity 6, my classmate and I explored the implications of abundant content for lifelong learning.For our topic, we chose to learn how to grow a tree along a flat surface in a predetermined pattern. A Google search for “How to grow a tree along a flat surface” led to the discovery that this technique was called ‘espalier’. Feeling inspired and informed, we used this term to search further. The photo below shows the ‘Images’ from the Google search engine, visually displaying a variety of espalier designs possible and the types of trees possible to work within this manner.

Looking at “all” results on Google, we found definitions, wikis, photo galleries, videos, and over 3 million results from a search of this term which we had not known even existed. This is an incredible abundance of content, and the next consideration was choosing which sources to read and watch.

My partner and I each chose to engage in different resources and then come together to explore what we found. We had read and watched videos on the topic until we felt we had a grasp on the basics of the technique.

History of Espalier

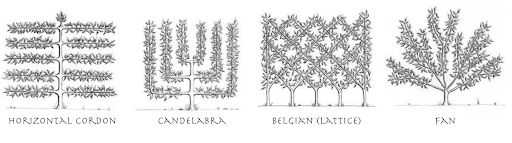

Espalier is the ancient horticultural practice of controlling plant growth. Encyclopedia Britannica states that the method was developed in Europe to encourage fruit production in climates that were not always compatible (2016). According to Wikipedia the word espalier is French and comes from the Italian word ‘spalliera’ which means “something to rest the shoulder against” (n.d.) Espalier can be used to make the garden visually appealing, replace the use of hedges or practiced to expose a tree to maximum amounts of sunlight or warmth within the garden space. The practice of espalier can extend the fruit-producing season. Branches are tied to a wire and extended out in various patterns.

Many varieties of fruit plants can be grown with the espalier technique, including pears, peaches, and grapes. Our post will focus on apples for simplicity.

Here are the details if you would like to try out espalier in your own backyard:

How to Espalier

- Choose your support structure: Supplies needed will depend on the location of planting. Bamboo, trellis, or a wall are good options for support structures depending on your space. Growing along a wall is reportedly the easiest method. If planting against a wall, position the tree 20-30 cm away from it to give the roots room to spread and increase airflow around the plant. If using a support structure, place the plant immediately in front of the structure. (Alberta Urban Garden Simple Organic and Sustainable, 2015)

- Dig a hole 1.5 to 2 times larger than your root ball. Place the tree in the hole using compost and root support additives as desired.

- Put up support structures aligning the lowest two branches to your lowest level of wiring. Finish planting the tree, making adjustments as needed to height.

- Use stretchy, gentle garden tape or velcro ties to hold branches to the wires.

- Prune branches accordingly to begin your desired espalier pattern.

Sounds simple, right? That is how we felt until we discussed and examined a few more resources. This post from the Fine Gardening (n.d.) website assumes some background or foundational knowledge that we just did not have, making it confusing and distracting to read. Mention of grafting two types of varietals (apples and pear) together to allow cross-pollination in a YouTube video from Alberta Urban Garden Simple Organic and Sustainable (2015) quickly led to us realizing that there is an assumption of foundational gardening knowledge in many of the resources we found.

An Abundance of Content

With over three million search engine results being returned in our original query, we were confident that there was enough information on the topic of espalier. With such an abundance of content, our next step was to individually use our digital literacy skills to evaluate the information we discovered to determine what was credible, up-to-date and met our current knowledge on the topic. While there are benefits to a vast amount of information on a topic, it can also be a detriment. Group members were able to relate this back to their teaching practices, where we use open educational resources (OER) in our course delivery. It is fantastic when the material is available; however, it can take a significant amount of time to curate the content that is most suitable for the learners. Weller supports that we require the “…appropriate teaching and learning approaches to make the best use of [knowledge abundance]” (2011). In keeping with his approach, we examined our learning activity through the lens of several learning pedagogies.

Upon completing our initial research, we used another affordance from the Net-Aware Theories of Learning, which included synchronous and asynchronous communication (Anderson, 2016). We started with asynchronous messaging using Slack as the communication channel, before moving into Google Hangouts for synchronous video chat. These tools were helpful to learn from each others experiences researching espalier and past experiences gardening and planting trees. While discussing, it became clear that we had different levels of experience gardening, which resulted in different selections of material. Additionally, our physical locations also played part in which material we found credible. For example, with one group member being located in British Columbia, they believed a video from Oregon, Washington was appropriate due to their similar climates, whereas a group member from Ontario worried that the difference in geographical location could impact the approach they would need to take in regards to soil, best time to plant the seeds, and other geographic factors. As the dialogue continued, we quickly realized that we were taking a Constructivism and Connectivism approach to this learning, as each group member was basing their learning on past experiences (Weller, 2011) and connecting information from both human and non-human entities (Weller, 2011).

From our individual searches and online discussions, it quickly became evident that even though an abundance of information can be beneficial to both learners and teachers, key skills are needed to leverage the content. Several of the skills needed can be found in digital literacy.

“Digital Literacy is the awareness, attitude and ability of individuals to appropriately use digital tools and facilities to identify, access, manage, integrate, evaluate, analyse and synthesize digital resources, construct new knowledge, create media expressions, and communicate with others, in the context of specific life situations, in order to enable constructive social action; and to reflect upon this process.” (Martin, 2006, p. 19)

Through knowledge on properly using the functionality of search engine tools, and evaluating and analyzing the results that are provided, learners have the ability to find and use the information that is most relevant to them in the abundance of material.

Now, we are left with the consideration of how to use these new skills to create something. As learners, using principles of constructivism, we have developed our mental models for how to grow our espalier apple trees and yet, we are not likely to fully integrate the knowledge until we attempt to make use of the content we found. At that stage we anticipate connection to Merrill’s principles of instruction (2002). Our research activity remains a learning exercise unless we actually attempt to solve a real-world problem by growing apple trees in our backyard. We would then activate any available previous knowledge, refer to demonstration in the form of video content and attempt to apply our knowledge (Merrill, 2002). No instructor will observe us, so we will need to keep connected to a network to ask questions, troubleshoot problems and integrate what we learned with what we come to know.

If we were instructors of this subject, we could consider the abundant resources as supplementary, to stimulate interest, questions, and reflection. The videos may be used as Weller suggests with Connectivism, to demonstrate diverse opinions (2011), challenge our learner to decide which sources to believe or connect partial pieces of resources into one full ‘story’ for learning. We agree with Weller (2011), that the new digital era of abundance requires a supportive pedagogy and that learners need skill sets of digital literacy and critical thinking to support knowledge transmission.

Co-authored by Brandon Carson and Christy Boyce

References

Alberta Urban Garden Simple Organic and Sustainable (2015), Espalier Apple Tree How to Plant and Trellis for Small Space Gardens. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QjPaXuwDkU4

Anderson, T., (2016). Chapter 3: Theories for Learning with Emerging Technologies. In Veletsianos, G. (Ed). Emergence and Innovation in Digital Learning: Foundations and Applications. Edmonton, AB: Athabasca University Press. Retrieved from http://www.aupress.ca/books/120258/ebook/03_Veletsianos_2016-Emergence_and_Innovation_in_Digital_Learning.pdf

Espalier (2016), In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved Sept 27, 2018, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/espalier

Espalier (n.d.), In Wikipedia. Retrieved Sept 24, 2018, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Espalier

Marshall, K., (2017) A step by step guide to espaliering fruit trees. Retrieved from https://www.stuff.co.nz/life-style/homed/garden/79922740/how-to-espalier-apple-and-pear-trees

Martin, A., (2006) Literacies for the digital age. In: Martin A and Madigan D (eds) Digital Literacies for Learning. London: Facet, 3–25.

Merrill, M. D., (2002). First principles of instruction. Educational Technology Research and Development, 50(3), 43-59.

Thevenot, P., (n.d.). How-To Espalier: Trained trees lend structural elegance to garden. Retrieved from https://www.finegardening.com/article/espalier

Weller, M., (2011). A pedagogy of abundance. Spanish Journal of Pedagogy, 249, 223–236. Retrieved from http://oro.open.ac.uk/28774/2/BB62B2.pdf